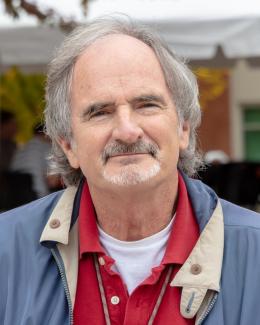

January 28, 2014 - After an illustrious 36-year career, energy policy research analyst David Greene retired late last year from The Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Greene's expertise has made him a frequently sought authority when energy is in the news. His observations, which often point to market forces' effects on oil prices, have invariably proven accurate in the long term.

In addition to generating a lengthy list of publications and honors as a corporate fellow and senior research staff member at ORNL's Center for Transportation Analysis, Greene has worked extensively with government, industry, and academia, including on the National Research Council's Transportation Research Board as an emeritus member of its energy and alternative fuels committees.

He was also the ORNL team lead for the development of FuelEconomy.gov, one of the US government’s most visited websites. Developed by DOE and the Environmental Protection Agency, the site hosts 48 million user sessions annually and is estimated to have helped the US reduce petroleum consumption by more than 928 million gallons in 2012.

Greene is a lifetime National Associate of the National Academies and was recognized as a contributor to the 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, which won a Nobel Peace Prize.

He continues to share a wealth of fuel-economy and energy-policy knowledge through his work at the Howard H. Baker Center for Public Policy as the senior fellow for energy and the environment and as a professor in the University of Tennessee’s economics department.

During an interview with Bill Cabage of ORNL Communications, Greene offers his vision for the future of the nation’s sustainable transportation architecture.

B.C.: What changed in 36 years—1977 to 2013?

Greene: In 1977 people weren't thinking about climate change and greenhouse gases as an urgent problem. Since then there has been a realization and understanding that we need to completely change the energy basis of our transportation systems over the next 40 to 50 years. Unfortunately, while our understanding may have changed, our practice hasn’t, and history tells us that’s going to be a challenge.

B.C.: Why is it so hard?

Greene: It’s not so much about the automobile but the energy. The internal combustion engine has become extremely sophisticated over the years, and we have a fuel supply system to support that.

Changing that petroleum energy infrastructure is going to be very difficult because of what systems analysts call “technology lock-in,” or the difficulty of introducing novel technologies like fuel cells or battery electric vehicles.

B.C.: What are the difficulties with new technologies?

Greene: It could take the industry 10 to 20 years to make a viable transition for several reasons: technology lock-in, the upfront expense of electric and hybrid cars, and the inconvenience of their shorter travel range before charging. All the while, companies that are selling cleaner, new technologies are losing money.

The good news is that if the estimates are right, you’re going to receive roughly 10 times the cost in benefits over the long run. The benefits to the environment, the climate, and energy security are probably going to save a significant amount of money on energy. It’s going to be cheaper to operate these vehicles.

B.C.: What are the benefits?

Greene: Obviously one benefit is the potential to reduce greenhouse gases. If you want to get to near-zero or 80% reduction in greenhouse gases [as proposed in a March 2013 National Research Council report], you can’t do that by burning petroleum, even if we make the vehicles as efficient as possible. Another is reducing petroleum dependence to increase our energy security. This is a hard problem for our political system because there’s a certain amount of pain up front.

We are doing well with improving energy efficiency—what I’ve spent my career on. About 30 years ago I realized that fuel economy standards were the most important thing in transportation and energy. Right now the standards are in good shape. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) just set appropriately strict standards that, more or less, call for doubling the efficiency of cars and light trucks by 2025.

B.C.: Will those standards be met through engine technologies, lightweight materials, going to electric vehicles, or hybrids?

Greene: All of the above. It will be mostly engine transmission and body technologies—like aerodynamics, rolling resistance, and engine efficiency and transmission improvements. But, I think they’re still going to need some degree of lightweight materials, and there will be more hybridization than EPA and the Department of Transportation have predicted.

Manufacturers spend hundreds of billions of dollars making improvements to these vehicles, and consumers save hundreds of billions of dollars every year. So even though we’re still roughly 95% dependent on petroleum, we’re using it more efficiently now, and we will continue doing so in the future.— edited by Sara Shoemaker and Katie Elyce Jones