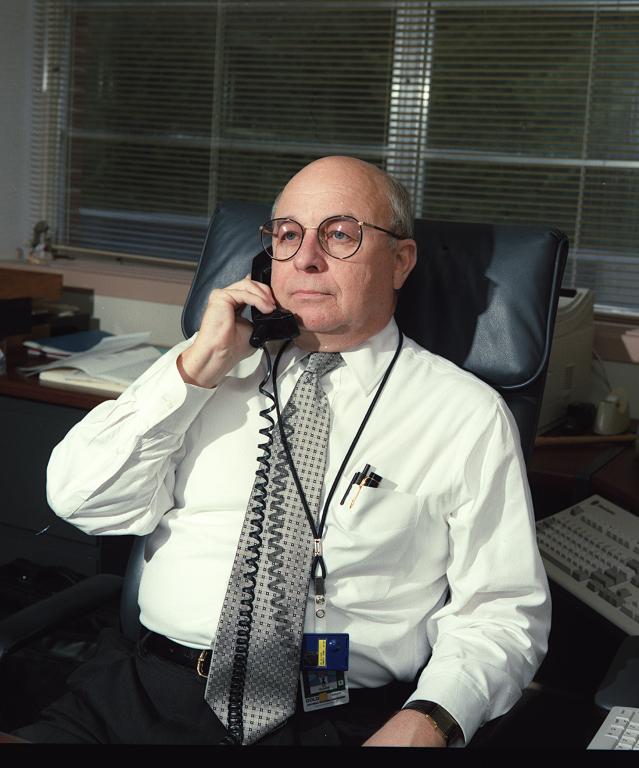

ORNL's Buddy Bland with the Intel Paragon XP/S 150 in 1995. Image credit: Curtis Boles, ORNL

ORNL has hosted four of the world’s top supercomputers since 2009, establishing the laboratory as a center for cutting-edge computational science and high-performance computing.

The laboratory’s journey to leadership in scientific computing began in the early 1990s from a nearly blank slate. At the close of the 1980s, computing resources at the laboratory were modest, to say the least.

Using an off-site computer

In fact, the most powerful computer available to ORNL researchers was several miles away at the K-25 uranium enrichment plant, one of the federal government’s three Oak Ridge facilities. ORNL’s director at the time, Al Trivelpiece, noted the gap in the lab’s computational capabilities and brought in the former chief scientist at the Air Force Research Laboratory, Ed Oliver, to create an Office of Laboratory Computing.

“As far as computer resources go, prior to 1985 there were pretty slim pickings at the lab,” Oliver said in a 1992 interview. “In 1985, K-25 acquired a Cray research computer, which was state-of-the-art equipment at the time and the state of the art of computing at the lab.”

The K-25 machine was available to lab researchers on a pay-by-the-hour basis, charged to the researcher’s division. Because of the cost, ORNL couldn’t fill up the Cray’s schedule, and it sat idle much of the time. Trivelpiece made a decision that led to a marked increase in demand for computing time and revealed an area of opportunity for the laboratory.

“Trivelpiece said that the lab should pay for the entire operating costs of the machine and allocate the computer’s resources to researchers at the lab,” Oliver said. “Instantly, it became 100% used, which proved that researchers needed computing resources.”

Early computing glory

ORNL hadn’t always lagged the computing field. In 1954, ORNL and Argonne National Laboratory unveiled the Oak Ridge Automatic Computer and Logical Engine, or ORACLE, a vacuum-tube-powered machine whose development was championed by ORNL’s then-research director, Alvin Weinberg, and Mathematics Panel head Alston Householder, who promoted it for complex calculations required by the Nuclear Airplane Project, a program to build a nuclear-powered bomber that could stay aloft for long periods of time.

For a brief time, ORACLE was the world’s fastest computer with the largest capacity for data storage, which was on paper tape. It reduced calculations that would take years on adding machines to minutes. The machine was also enlisted for tasks such as business operations and financial accounting. By the early 1960s, the one-of-a-kind machine was obsolete, and the laboratory began leasing commercial mainframe computers.

Tapping the power of simulation

Meanwhile, the promise of computational simulation as a scientific tool was on the horizon. In 1962, ORNL physicists used a computer model to simulate ions bombarding crystalline metals. One simulation showed a particle passing through a tunnel in the model's atomic structure, revealing an effect known as ion channeling. Experiments verified the prediction, leading to the ion implantation technology used by the semiconductor industry and to improve durability of materials used, for example, in artificial joints.

Forward to the 1990s: The successful switch to lab-funded computing fed ORNL’s ambitions in high-performance, parallel computing. In 1992, DOE selected ORNL as one of two High Performance Computing Research Centers. By 1995, ORNL was again at the top of the computing heap with the rollout of Intel Paragon XP/S, a 150-gigaflop machine (able to do 150 billion calculations each second) that was installed on the second floor of Building 4500 North, where most of ORNL’s computing resources were located.

The Intel Paragon was one of the world’s fastest for a time. It was preceded by a Kendall Square Research machine, the KSR-1, which could be considered the laboratory’s first high-performance computer. A short time later, in 1992, a smaller Intel machine, the Paragon XP/S 35, arrived, the result of a cooperative R&D agreement with Intel. The Intel Paragon XP/S 150 followed a few years later, to great fanfare.

By 1997, Oliver was associate director of an eclectic combination of computing, robotics and education and making plans for ORNL’s next foray in the supercomputing race — a progression to trillions of operations per second.

Getting ready for the big ones

“A multiteraflop machine can cost $40 or $50 million. They are physically bigger, so you need facilities, more space,” Oliver said in 1998.

One of the lessons learned with Paragon was that supercomputers required significant investments in infrastructure. In 2000, UT-Battelle arrived as ORNL’s managing contractor (on behalf of the Department of Energy’s Office of Science) with a modernization plan that ultimately included a privately funded Computational Sciences Building with the infrastructure necessary to power and cool the voracious processors. In the meantime, Oliver had moved to the Office of Science as associate director for Advanced Scientific Computing Research, providing an agencywide platform for his vision for high-performance computing.

Earth Simulator was seismic

In 2002, Japan rocked the computing world with its Earth Simulator, a supercomputer dedicated to climate science research that outperformed computers in the United States by factors of 10. Then-Office of Science Director Ray Orbach, in a visit to ORNL, called the U.S. loss of computing supremacy “catastrophic” and announced that ORNL would serve as the testbed for a new supercomputer architecture intended specifically for scientific applications, which represented a new approach to the previous “one size fits all.”

By 2004, ORNL had been selected by DOE to lead a partnership to build the world’s most powerful supercomputer through the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, housed in the newly constructed Computational Sciences Building’s computing bay. Around the same time, the lab dedicated its state-funded Joint Institute for Computational Sciences, located near the Computational Sciences Building.

ORNL’s Jaguar, a Cray system, came online in 2005. Following an upgrade, it topped the TOP500 ranking of supercomputers in November 2009. Jaguar was upgraded and converted to Titan — in 2012 Titan also placed first on the TOP500. Summit followed in 2018, debuting at No. 1. Frontier, a supercomputer uniquely suited as a powerful artificial intelligence tool for science, broke the exascale barrier in 2022, performing more than a billion billion calculations a second.

Ed Oliver did not live to see the culmination of what he helped begin, described by then-ORNL Associate Laboratory Director for Computing and Computational Science Thomas Zacharia upon Oliver’s death in 2008:

"It was Ed Oliver's vision that Oak Ridge National Laboratory would one day be the world leader in scientific computing and its application to solving some of the most compelling problems that face humanity. He always had high expectations of the promise of supercomputing and therefore had high expectations of ORNL." — Bill Cabage

Further reading: “Tracing throughlines: A brief history of artificial intelligence at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.”