by Tim Gawne

gawnetj@ornl.gov

Oak Ridge in its earliest days was a quintessential planned community, and a gated one at that.

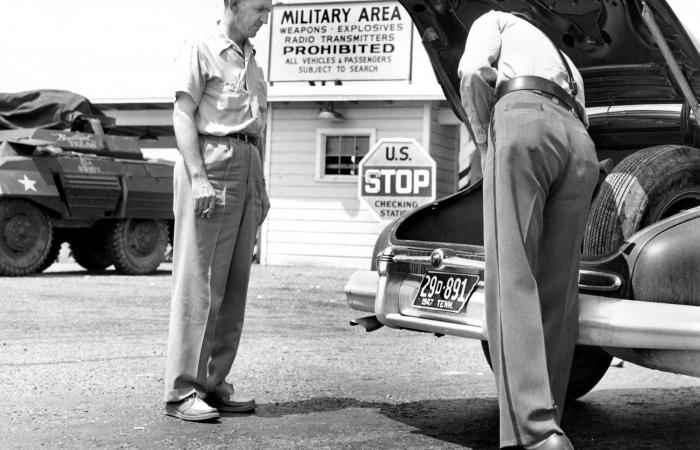

Born of the wartime necessity to house the thousands of workers who would construct and operate the region’s three Manhattan Project facilities, the city itself was a secret. It had gates, too—guarded ones.

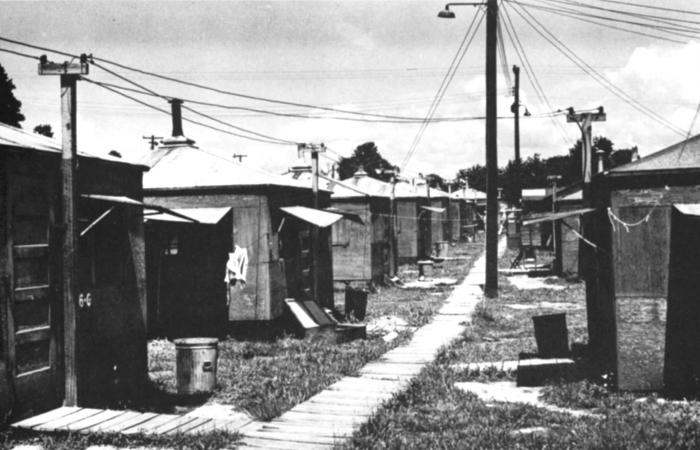

At its peak, Oak Ridge was home to 75,000 men, women and children, a number that far exceeded the government’s initial projections. As a result, the town hosted a patchwork of housing types, from prefabricated houses to dormitories, trailers and the euphemistically named “victory cottages,” which each bunked five workers around a coal stove. If you were lucky enough to land a spot in a victory cottage, you also found yourself sharing bathroom and shower facilities with the rest of the neighborhood.

Despite its rushed construction, Oak Ridge had many of the same facilities as other communities in the 1940s: schools, a pool, recreation centers, churches, cafeterias and a full-service hospital. It also had a few features other communities lacked: security fencing, a curfew, armed guards at each town entrance, and its own military intelligence force.

It was a love-it-or-hate-it kind of place; you either saw the frontier town it appeared to be, or you saw the thriving community it had the potential to become. While many early residents were happy to bid it goodbye when they had the chance, the ones who stayed carried a sense of pride for having roughed it in “Dogpatch.”

Nobel Prize-winning physicist Arthur Compton belonged to the former group. In his book The Atomic Quest, Compton recalled a rainy ride from the nearby city of Knoxville carrying a cake to his child’s birthday party. A fellow passenger looked down at his muddy boots and said, “Oh, you are from that place.” Compton was happy to put distance between himself and Oak Ridge once the war no longer required his services.

Another early staffer—the lab’s chemistry director at the time—was even more blunt. His view of the residential area was so dim that he suggested the Army build a better development next to the lab called “Clinton Village.”

Beyond housing, the bigger obstacle to long-term sustainability was that Oak Ridge’s three plants—X-10 (which eventually became ORNL), Y-12 and K-25—faced an uncertain future until 1949, when their continued operation was guaranteed by the newly formed Atomic Energy Commission.

The town would have growing pains. For one, it had to choose whether to remain behind the security perimeter established during the war or to open up and let the public in. Some opposed opening the town, but they were in the minority. On March 19, 1949, at what was Elza Gate, a magnesium ribbon was ceremoniously electrified by ORNL’s Graphite Reactor, the world’s first continually operating nuclear reactor.

The ribbon split in a blaze, formally opening the city to the public. The celebration included parades and public tours. Good Housekeeping magazine even came out and gave the town a good review and a rating of “must see.