Scientists have determined that a rare element found in some of the oldest solids in the solar system, such as meteorites, and previously thought to have been forged in supernova explosions, actually predate such cosmic events, challenging long-held theories about its origin.

Scientists at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory led studies of the radioactive isotope beryllium-10, which existed when the solar system came into being some 4.5 to 5 billion years ago. They probed whether this isotope can be formed in sufficient quantities during the massive explosions of gigantic stars in their death throes, called supernovae.

“It is unlikely that such a stellar explosion is the main source for this isotope, as it is observed in the early solar system,” said Raphael Hix, an ORNL nuclear astrophysicist who participated in the study published in the journal Physical Review C. The findings “help us to understand the history of the solar system and the galaxy as a whole.”

The scientists speculate that beryllium-10 is more likely the result of what’s known as cosmic ray spallation — an interaction with the random and ubiquitous high-energy protons and other isotopes, such as carbon-12, that race in all directions throughout the universe at almost the speed of light.

When a star dies, it ejects atoms from its core into the interstellar medium, which is low-density matter that fills the space between stars in a galaxy. The process of making isotopes and elements in stars is referred to as nucleosynthesis. Eventually, portions of the interstellar medium will collect to form the next generation of stars and their associated planets. Included in that atomic soup is carbon-12, which occasionally collides with cosmic rays.

When these high-energy rays collide with carbon-12 atoms, “it literally breaks the nucleus apart, and what’s left can include beryllium-10,” Hix said.

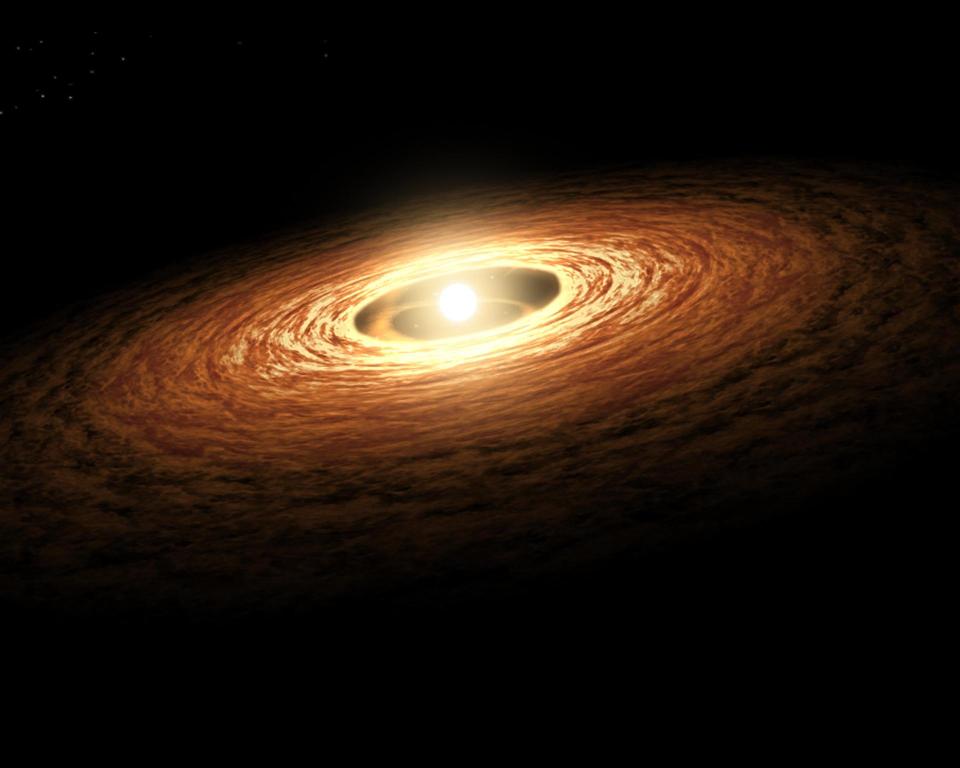

About 4.5 billion years ago, the solar system formed from the collapse of a humongous cloud of gaseous molecules, which created a swirling disk of material known as the solar nebula. Over millions of years, gravity caused the material to coalesce, leading to the formation of the sun and all its planets. Beryllium-10 has a relatively short half-life – the time taken for half the number of radioactive nuclei to decay – of 1.4 million years. That means any beryllium-10 found on Earth today was created long after the solar system formed. However, in some meteorites, scientists find boron-10, a decay product of beryllium-10. The presence of boron-10 with nonradioactive beryllium isotopes implies that freshly made beryllium-10 was already present in the solar system when it formed.

Hix and then-postdoctoral researcher Andre Sieverding, now a staff scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, used computational resources at DOE’s National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, or NERSC, to calculate the amounts of different elements and isotopes produced by supernova explosions. Supernova explosions can occur in stars that are anywhere from 10 to 25 times as massive as the sun. They received help from University of Tennessee undergraduate Daniel Zetterberg working at ORNL, and colleagues at the University of Notre Dame.

If short-lived isotopes, such as beryllium-10, can come from supernova explosions, then, according to prevailing scientific thought, this would support the idea that the formation of the solar system was directly triggered by a supernova.

However, recent calculations challenge this idea, at least for beryllium-10. New data from nuclear experiments, where nuclei are collided to create new nuclei, uncovered nuclear properties that enhance the reaction rate that turns beryllium-10 into other isotopes. This rate replaces an estimate for the reaction rate that is more than 50 years old. Measuring it in the lab with improved experiments gives a more accurate and detailed picture. The new reaction rates calculated by the scientists are up to 33 times faster than those obtained from prior experiments.

Sieverding, Zetterberg and Hix determined the new rate was fast enough to effectively destroy beryllium-10 in supernovae. As a result, a supernova collapse and explosion “is unlikely to produce enough beryllium-10 to explain the observed beryllium-10 in meteorites,” Hix said.

“This makes it almost certain that spallation really is the source for beryillium-10,” Hix added. “Unless there are major changes in the models for the structure of stars in this mass range, these findings point towards a need for another source of beryllium-10.”

Sieverding said, “As a result, it is unlikely that a supernova was the source of the beryllium-10 in the early solar system.”

The study was a collaboration involving several institutions. ORNL’s Sieverding, Hix and Zetterberg made the astrophysical simulations and nucleosynthesis calculations. At the University of Notre Dame, Jaspreet Randhawa, Tan Ahn and Richard James deBoer interpreted the experimental data to extract the relevant reaction rate. At the Technical University of Darmstadt in Germany, Riccardo Mancino and Gabriel Martinez-Pinedo made theoretical calculations of reaction rates. Since the rate was too slow to be measured directly, their experiments measured properties of the nuclei, and theorists turned these properties into a reaction rate.

The work was funded by the DOE Office of Science.

UT-Battelle manages ORNL for DOE’s Office of Science, the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States. DOE’s Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit energy.gov/science. — Lawrence Bernard