Time Warp

Most of us grew up watching TV and movies that depicted artificial intelligence in a less than comforting light. From 1927’s “Metropolis” to last year’s “Blade Runner 2049,” Hollywood has imagined AI as a force for threatening the world, enslaving humanity and being an all-around bad actor.

These destructive, self-aware machines make for excellent theater, of course, but they obscure the benefits we stand to gain from AI, especially in research. Even as the capabilities of computing and data analysis ballooned over the decades, people often had difficulty distinguishing real AI from the killer robots of the silver screen.

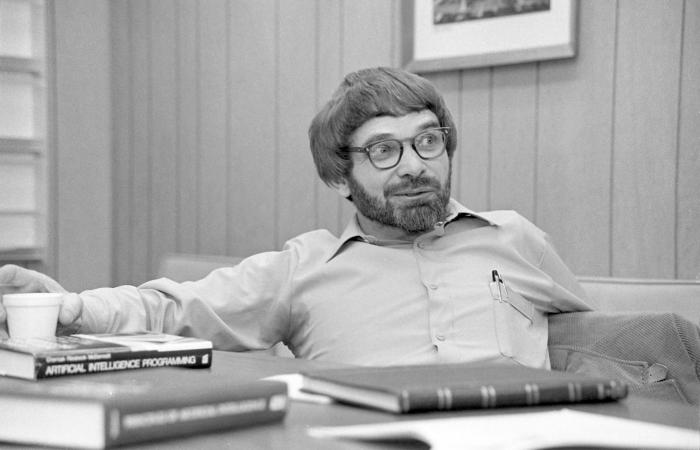

“It is always interesting to observe the response of an audience introduced to the research field called ‘artificial intelligence,’” ORNL AI pioneer Carroll Johnson noted in 1981. “The very term implies that a computer can be programmed to reason like a person. The concept may seem frightening, preposterous or stimulating depending upon the listener’s viewpoint, and these reactions are often reflected in the comments from the audience.”

Johnson launched the lab’s earliest AI effort after returning in 1976 from a sabbatical at Stanford University. Stanford had developed CRYSALIS, an AI effort that infers the atomic structure of protein molecules, and Johnson helped guide that effort with his expertise in crystallography.

In October 1979 he assembled a panel of ORNL researchers—both domain scientists and computer engineers—to launch the Oak Ridge Applied Artificial Intelligence Project. Its goal: to evaluate AI as a tool for supercharging research at the lab.

One panel member was Michelle Buchanan, then an early career analytical chemist, now the lab’s deputy for science and technology. Buchanan worked with software called EXPERT, developed at Rutgers University for use in spectroscopy.

Buchanan says the project remains one of the most rewarding activities of her career at the lab. She recalls the meticulous interviews Johnson would set up to capture the interpretation of infrared, nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectral data. This attention to detail led Johnson to produce nearly 1,500 pages of notes.

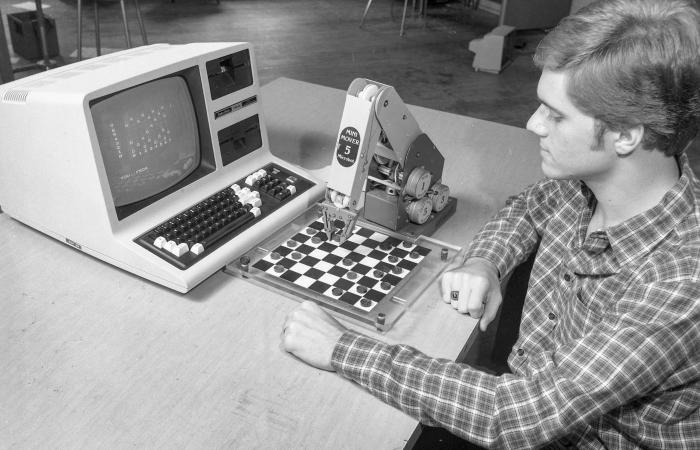

Johnson saw the potential for an AI system like the adapted EXPERT to work with a computer-controlled instrument such as a mass spectrometer and provide real-time data capture and analysis.

For those reading Johnson’s notes, the concepts, principles and domains of potential application are not that far removed from our aspirations today. The only observable difference appears to be the scale of both the applications being deployed and the systems on which they are deployed. ORNL’s Titan supercomputer—a Cray XK7—is more than 150 million times faster than Cray’s flagship system at the time Johnson formed his panel in 1979.

With this greater capacity, we are seeing Johnson’s dream become reality.